The Call to Adventure

The following passage from Michael Friendly's Visions and Re-visions of Charles Joseph Minard jumped off the page when I first read it it six weeks ago:

Already primed with an enthusiasm for the broader catalog of Minard's work, discovering that his contemporaries were also big fans spiked my curiosity gap. The thought that a Minard map adorned a French oil painting in a gallery somewhere was just too rich.

Immediately I took to Google in hopes of seeing this MacGuffin, but quickly accepted that obvious keywords would not lead me to the prize I sought. Returning to Friendly's paper I noted his source - Chevallier, 1871 - and found that the extensive obituary of Minard includes this line:

Reading this source text called me to an adventure to find this painting, not knowing if it even existed.

Crossing the Threshold

Minard's obituary contained some promising clues: a Minister of Public Works? a painting exhibition? about one decade before 1871? Wikipedia contains a table of Ministres français des Travaux publics and the Second Empire years of service of Eugène Rouher seemed to overlap perfectly with the the target year of 1861:

Another round of Googling for portraits of M. Rouher (and some of his colleagues) yielded nothing and I knew I had exhausted my capabilities. It was time to ask for help.

The library of l'Ecole nationale des ponts et chaussée (the National School of Bridges and Roads, Minard's home institution) houses the most complete collection of Minard's work, some of which was given by Minard himself. You can explore its entire collection here. I reached out through Twitter and soon found myself in correspondence with Anne Lacourt, responsable des archives et des collections d'objets et mobilier (responsible for archives and collections of objects and furniture).

Madame Lacourt immediately added some context to the clues I presented to her. The painting exhibition was likely a salon exhibition by l'Académie des Beaux-Arts. These famous exhibits happened every couple of years and were massive affairs. The 1861 Paris exhibition presented over 4,000 jury-selected works of art across 38 galleries. This event was a cultural happening that included a costume party and other festivities (perhaps analogous to Burning Man or SXSW).

Madame Lacourt continued by agreeing that Minister Rouher was indeed a possible subject match, at the same time acknowledging the painting could also be of one of his predecessors. Most importantly, she too was intrigued by the possibility of a painting with a Minard. Madame Lacourt generously offered to contact her colleagues at the Académie des Beaux-Arts and, just like that, I felt like France's best historians had joined the hunt for the painting with the Minard.

Magical Helpers

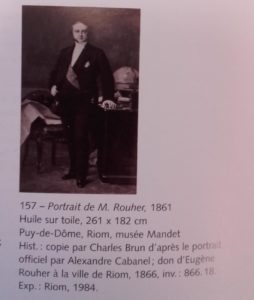

It did not take long for the search to pick up speed. Anne Lacourt's contact at the Académie brought in the INHA (Institut national d'histoire de l'art) and they were able to provide the next important lead: there was a portrait of M. Rouher by Alexandre Cabanel that was presented at the 1861 Salon. The original painting's location is unknown (oh no!) but a copy survives at the Musée Mandet in Riom, France. Further, a thumbnail image of this copy was scanned from a catalog of Cabanel's work - our first visual clue!:

This thumbnail raised the excitement of the search to a new level. Rouher is depicted with a globe (surely a fan of maps, no?!) and a large something draped over a chair. It is impossible to distinguish what this mysterious document is from the catalog thumbnail. Could it be a Minard? To answer this question and complete our quest we would have to go to Riom.

Jean-Marie Lagnel, Creative Director at data visualization Studio V2 in Paris, was recruited to the hunt. He hit the phone and worked his way over several days to Riom's Chief Curator of Heritage. Communicating our interest in their portrait of M. Rouher, M. Lagnel learned that the painting indeed survived, but that there was no existing image of it with high enough quality to see any details of its included document. We were asked to wait for new photographs to be taken.

The Ultimate Boon

On my way to the Tapestry data storytelling conference in St. Augustine, Florida I received an e-mail with some very special attachments and a one line message from Jean-Marie Lagnel: Hi, look at this : )

The painting had been found. The mysterious document draped over the chair was a map. It was a Minard!

Upon closer inspection those familiar with Minard's catalog will recognize it as one of his maps depicting the flow of goods to Paris via waterways and railroads.

Detail: Charles Brun. Portrait de M. Rouher. 1861. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Musée Mandet, Riom, France.

Before I could exclaim my excitement with the painting, M. Lagnel has already identified exactly which Minard map was included, an 1858 flow map titled Carte figurative et approximative des tonnages de marchandises qui ont circulé en 1857 sur les voies d'eau et de fer de l'Empire français (Figurative and approximate map of the tonnages of goods which circulated in 1857 on the waterways and railways of the French Empire). A high quality version of this particular map can be inspected at the library of l'Ecole nationale des ponts et chaussées. I have created a short animation to show how well the painting and map match:

Minard's series on the circulation of merchandise is epic. It contains many maps that display both an evolution in his charting style and track a longitudinal data story. Learn more about Minard's catalog and families of maps by reading this article's companion piece, Seeking Minard.

Reflection Upon Return

Finding this painting paid off in many ways. Of course it was the perfect capstone to my investigation into Charles Joseph Minard - novel proof of how special he really is, not only through our data-fueled lens but also from the perspective of his contemporaries. It feels good to know that his work was celebrated and appreciated in his day.

But the journey was meaningful because of the people who I got to share it with, particularly Anne Lacourt and Jean-Marie Lagnel, but also other "magical helpers" who I may never meet. To complete my monomyth metaphor for this tale I should also note my amazement with our modern "supernatural aids" that made this search possible. Without networks and tools like Twitter and Google Translate I don't think I would have gotten far enough for the magical helpers to step in. It's easy to take the Internet for granted, but some days it really shines.

As a last personal note, I have to mention that my interest in this painting would never have been piqued without a passion for the beautiful objects that history has bestowed on us - something my parents taught to me. Family vacations in the Andrews household always involved visiting some collection of antiques, and often put us behind the scenes in the archives of some museum. My parents showed me the joy and excitement an object can bring by serving as a rallying point for shared stories and wonder. I hope that by telling the story of the painting with the Minard I was able to share some of this excitement with you.

Mom and Dad in the basement of the Legion of Honor during their last trip to San Francisco.

Update: it was very exciting to see Betsy Mason include this investigation of Minard in her excellent The Underappreciated Man Behind the “Best Graphic Ever Produced” at National Geographic's All Over The Map.

Info We Trust is an award-winning ‘data adventure’ exploring how to better humanize information. Data storyteller RJ Andrews is based in San Francisco. Please let me know what you think via Twitter @infowetrust or the contact page.

No comments.