Colossal Chronography

Frances Harriet Lightfoot's 1831 marvel.

This essay was first published in Chartography, a newsletter about information-design insights and inspiration.

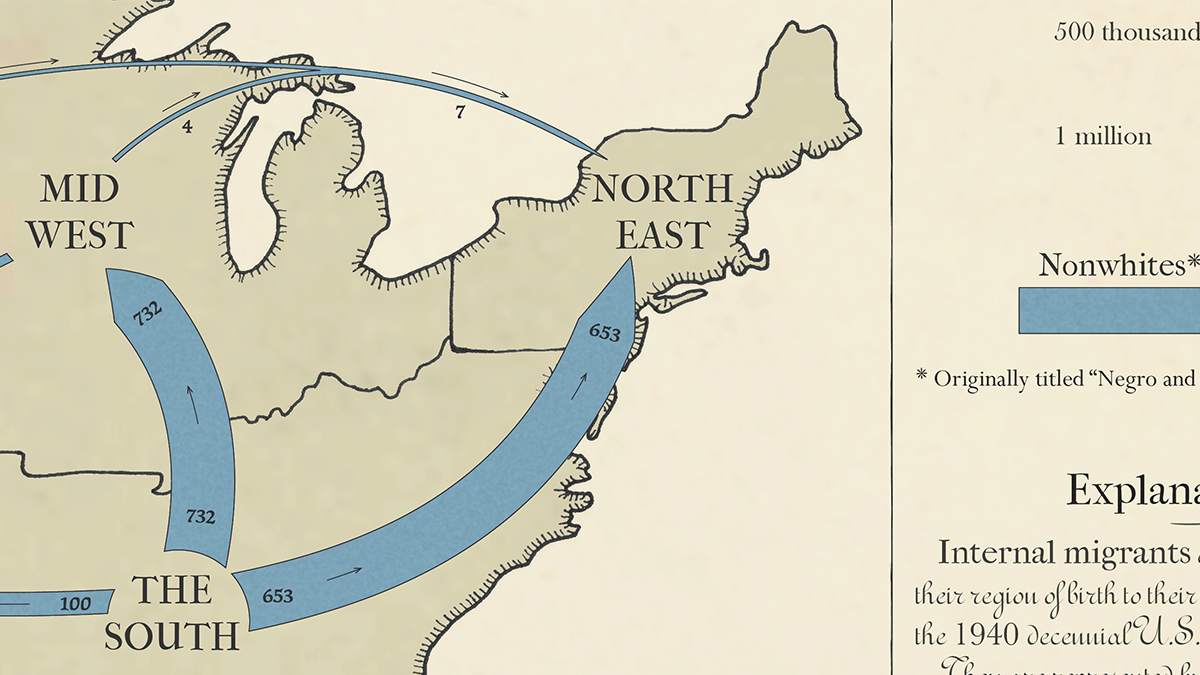

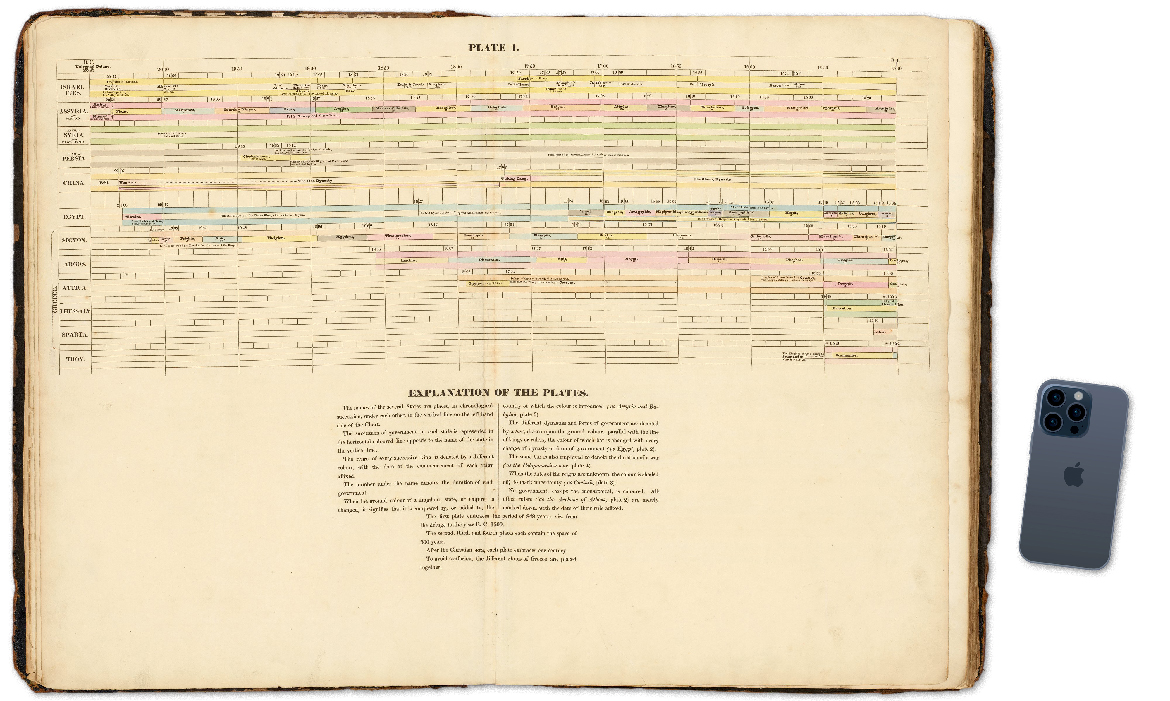

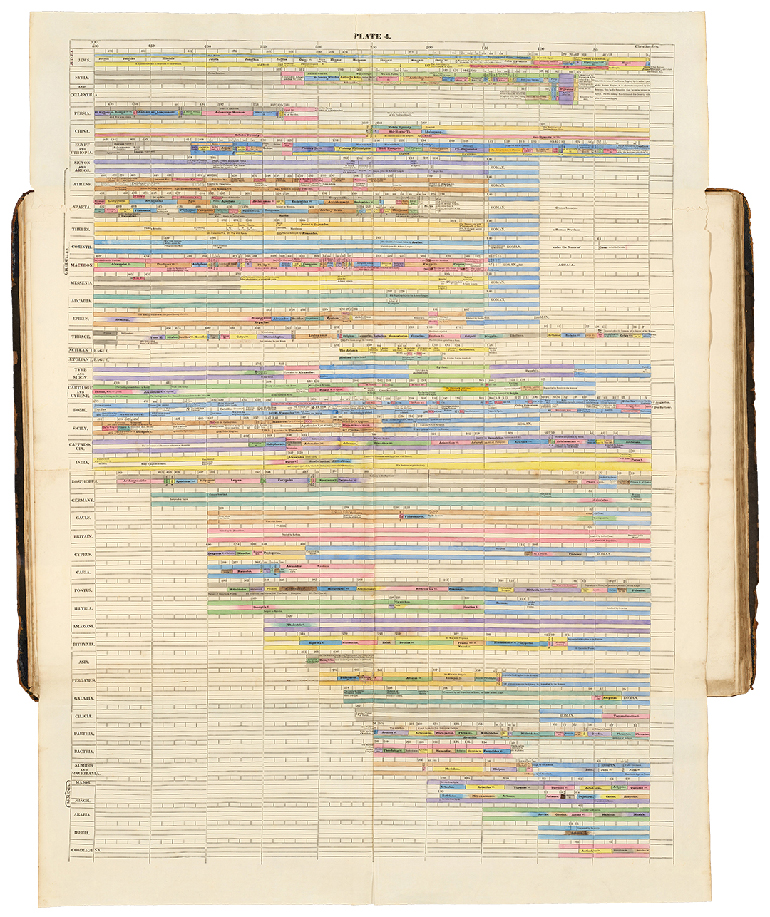

One reason to envy long-past information designers is the big canvases they got to play with. Consider this 1831 timeline next to my iPhone—it’s big, isn’t it?

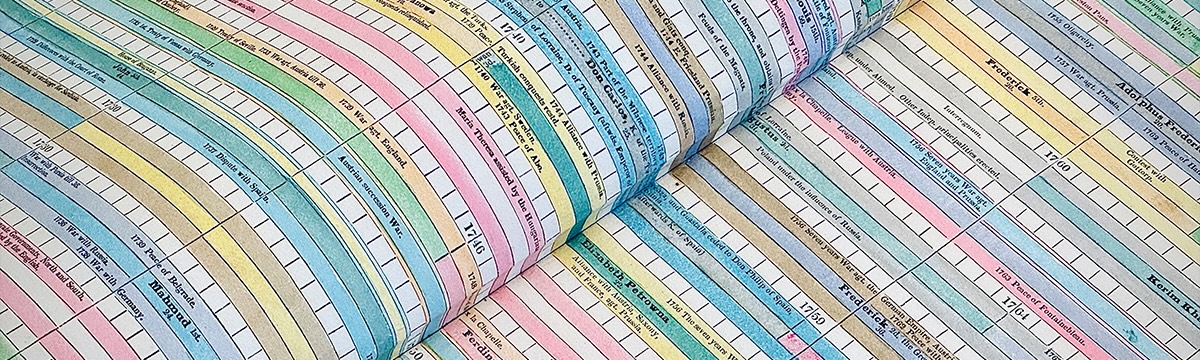

Time flows to the right, with different empires occupying their own lanes, each marked by vivid colors. Perhaps you’ve seen some design similar to this before.

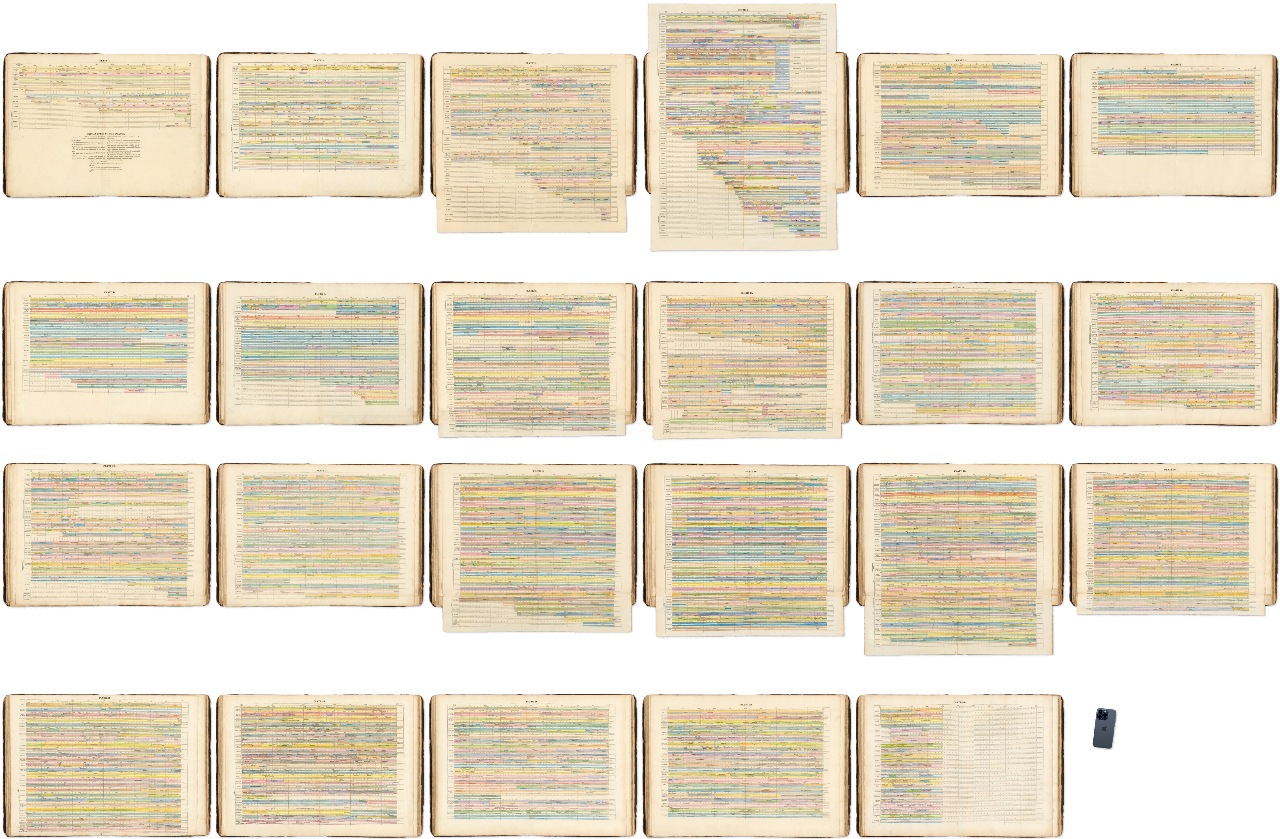

Yet, if you peer closer, you’ll notice this is only Plate 1. The timeline stretches on… and on!

An Embellished Chart of General History and Chronology is an extraordinary piece of information design from 1831 London. In the history of colorful timelines, this one stands out in several ways:

- It is immense

- It is relatively early.

- It seems unknown to modern researchers.

- It was created by a woman.

Frances Harriet Lightfoot published her chronology when she was 29 years old. More on her in a bit.

The Design

Seven of the chronology’s plates fold out, including the towering Plate 4, below. It’s a vertical monster about 3 feet tall covering the final 500 years of the BC era. I count 134 distinct geopolitical rows.

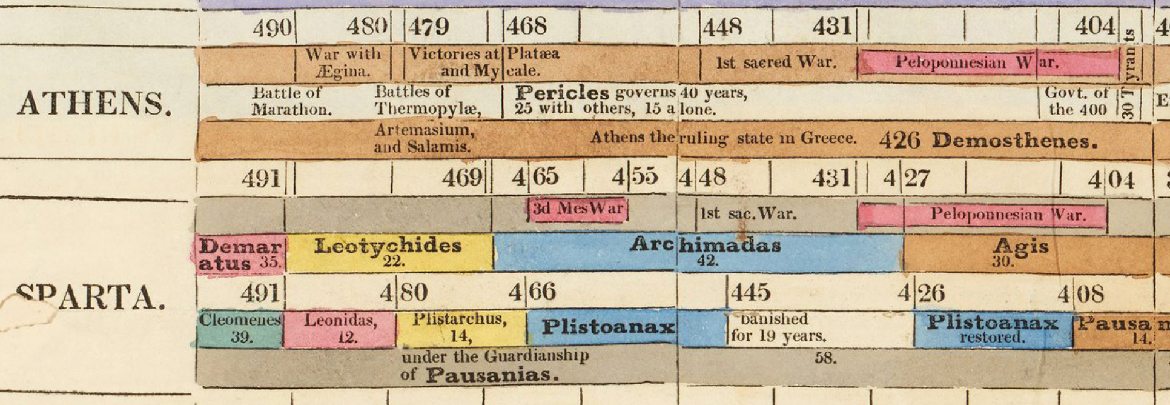

If we zoom to the Golden Age of Athens on this plate you can appreciate the chronology’s impressive level of detail.

I particularly like how years specific to events are labeled.

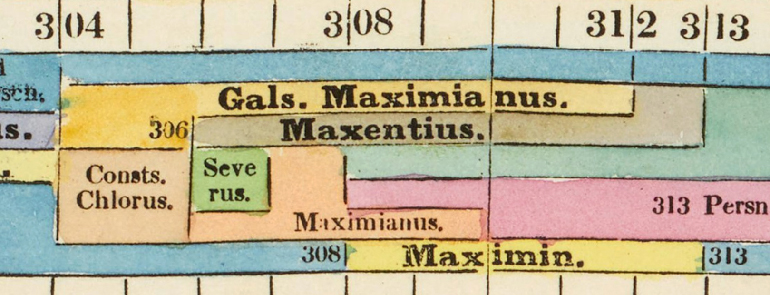

In the AD era, Lightfoot’s design shifts time scales, with the same horizontal space detailing only 100 years, giving five times more room to illustrate history.

If we fly to the Roman Civil wars of the Tetrarchy, we can see how crazy a single lane can get!

Lightfoot’s volume opens with a three-paragraph preface in which she refers to herself in the third person:

. . . a work which is the offspring of research rather than of genius; and it appeared to her that the study of Chronology might be rendered more attractive to the rising generation, by a new arrangement, in the form of the Chronological Tables, combining simplicity with comprehensiveness. . . .

She also includes a list of subscribing sponsors along with dozens of reference pages.

These are divided into a long Table of Remarkable Events Not Noticed in the Chart and another table of Celebrated Persons grouped by theme—geographers, mathematicians, poets, and so on.

Lightfoot credits herself for the “plan” (the design) and acknowledges unnamed predecessors for the historical data, noting that she updated their work with her own research.

For this essay, I studied two copies of Lightfoot’s chronology. Most of the images you see come from photographs recently published by the David Rumsey Map Collection. I also consulted my own copy, and it’s fascinating to compare the differences in their hand-coloring.

The experience of discovering and reading this work is, to me, overwhelming. While its colors captivate, my deepest curiosity lies with its creator.

Who is Miss Lightfoot? How did she come to create such a monumental work of information design? And why have I never heard of her?

After days reading census records, newspapers, and other public documents, I have pieced together what I believe is her first biographical sketch.

Meet Frances Harriet

Frances Harriet Lightfoot was born around 1802 in Lambeth, Surrey. She was a distinguished composer and author whose works left a broad mark on the 19th century.

Lightfoot finalized the publication of her chronology on October 1st, 1831, from 14 Great James Street, New Palace, London. The Sun newspaper covered it the following month:

This work is so ingeniously arranged as to afford at once glance a clear and comprehensive representation of the state of all known contemporary nations, from the Deluge to the present period. A system better calculated to facilitate the acquisition of this most puzzling, yet most valuable part of historical knowledge could hardly, we should think, be imagined; but we are not aware of even the existence of another book which possesses similar advantages, or has any claims to rival it in the public estimation.—Sun newspaper, 30 November 1831

By my count, 136 copies of the chronology were listed for subscribers, including one for a resident of Willsbridge House, hinting at an early connection to Lightfoot’s future home. The subscriber list comprised a diverse and high-status group—dukes, earls, admirals, baronets, and notable politicians—reflecting the publication’s strong support among society’s elite. Today, approximately 15 copies of the work survive, according to WorldCat, with ten in the UK and five in the USA.

Professorial Ventures

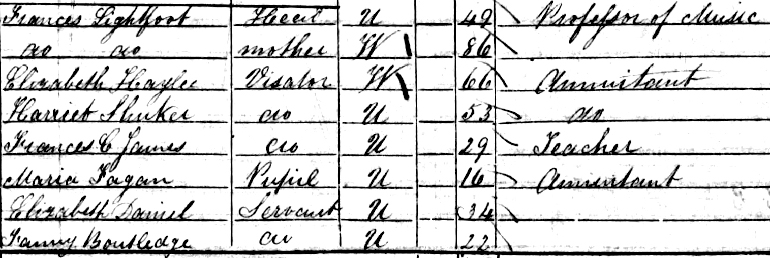

A decade after the chronology’s publication, in 1841, Lightfoot was living with her parents, both still residing at 14 James Street in the parish of St Margaret, Westminster, Middlesex. In addition to her parents, Frances Harriet, listed as a “Professor of Music,” shared the household with three other women.

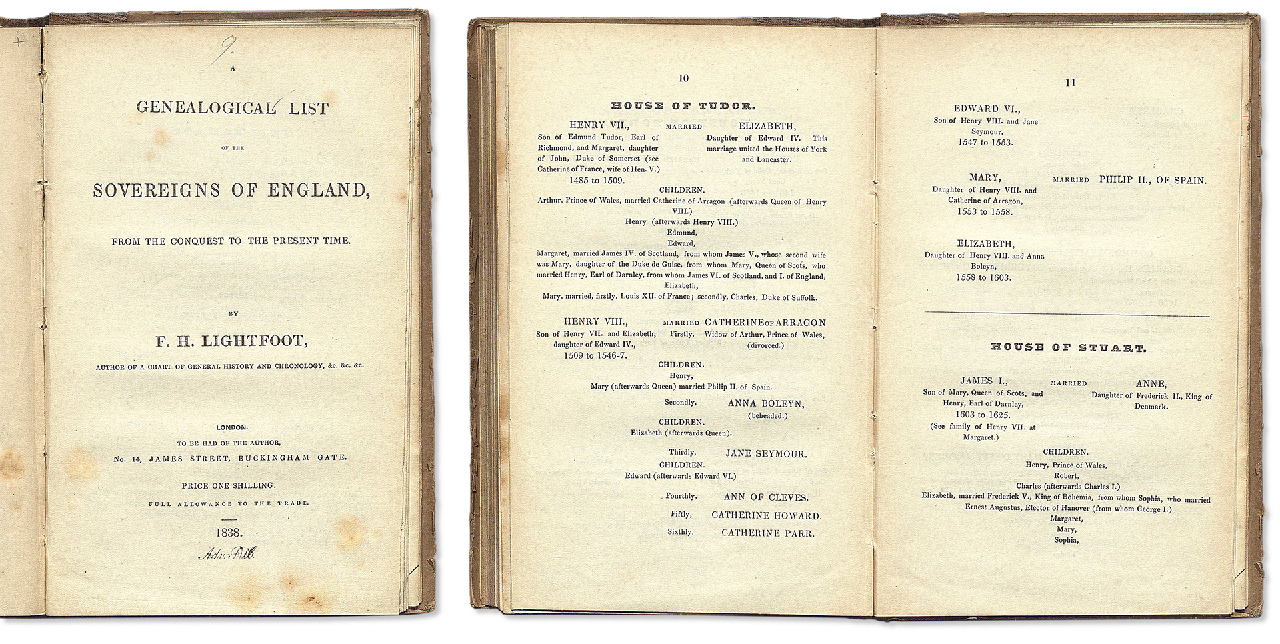

Besides her 1831 chronology, Lightfoot also authored A genealogical list of the sovereigns of England (1838), a stylized table spanning 13 pages.

In 1845, she published French Participles Explained and Made Easy, showcasing her diverse intellectual interests.

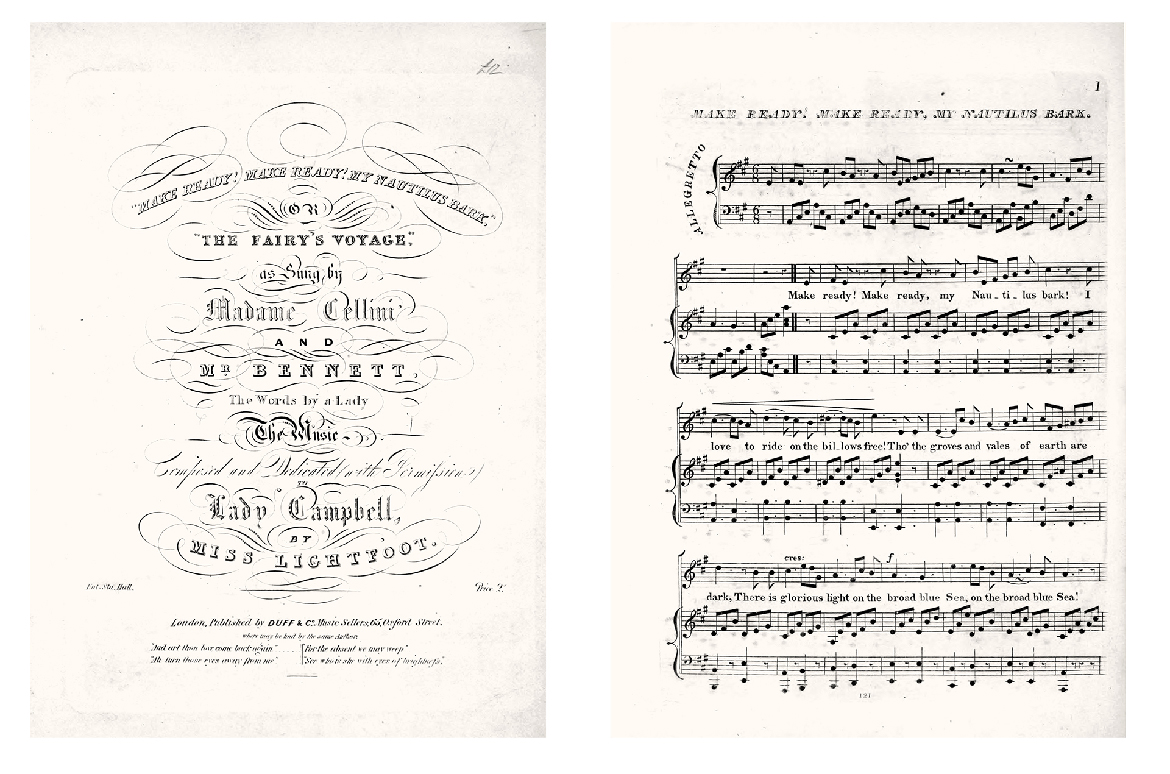

However, Lightfoot was most prolific in composing musical scores. Between 1828 and 1855, her works included ballads, songs, and duets, often created in collaboration with women lyricists.

These musical pursuits align with her professional occupation as a “Professor of Music” and her active role in education, as reflected in census records that often list pupils and other boarders in her household.

By 1851, Frances Harriet had moved to 41 Cadogan Place in the prestigious Belgravia neighborhood of London. There, she was head of a household that included her 86-year-old mother, along with several other women—a visiting teacher, a pupil, and servants. In this new residence, she continued her professional pursuits, once again listed as a “Professor of Music,” underscoring her enduring commitment to education and the arts.

In 1861, Frances Harriet was recorded as a "School Mistress" at Willsbridge House in Bitton and Oldland. This residence, later known as Willsbridge Castle, carries a notable musical heritage. Built around 1730 for John Pearsall, the house remained in the Pearsall family, including composer Robert Lucas de Pearsall, renowned for his madrigals and Anglican church music. The house's connection to such a prominent musical figure aligns with Frances Harriet's own musical background.

In both 1851 and 1861 censuses, Lightfoot’s household included teachers and students, all women, reflecting her ongoing commitment to education and music.

Final Years and Legacy

Frances Harriet Lightfoot passed away aged 71 years old on July 14, 1873, at Willsbridge House. She was buried five days later at St. Mary Churchyard, Bitton, South Gloucestershire. Her will named two executors, with an estate valued under £600.

Lightfoot’s one-acre residence was auctioned the following January at the White Lion Hotel in Bristol. Willsbridge House was described as a substantial mansion with extensive amenities including stables, a coach house, a detached laundry, and well-maintained gardens, highlighted the grandeur of her home. The house itself featured spacious cellars, multiple reception rooms, numerous bedrooms, and a garden stocked with fruit trees and an abundant mineral spring. Its proximity to the Bitton Station on the Midland Railway further underscored its prime location.

Public records sketch a picture of Frances Harriet Lightfoot as a well-connected and intellectually versatile person with a keen interest in music. They also suggest a woman who maintained significant properties and professional roles. The consistent reference to Lightfoot as a spinster in various documents, including her will, indicates she remained unmarried throughout her life, which was relatively uncommon for women of her time and social status.

Frances Harriet Lightfoot's life reflects a woman deeply embedded in the intellectual and artistic fabric of her time. I am excited to learn about what you find studying her colossal chronology at DavidRumsey.com.

Lightfoot is a good reminder that the constellation of spectacular historic designs is only partially visible to our modern eyes. I look forward to seeing more.