Florence Nightingale is a Design Hero

May her light forever shine bright.

This article inspired years of research, writing, and discovery about Florence Nighitngale's persuasive information graphics which ultimately yielded the book Florence Nightingale, Mortality and Health Diagrams (2022), which you can learn more about at Visionary Press.

While the following article does not incorporate corrections or additions learned from this effort, it is still an OK introduction to Nightingale's contributions.

Founder of modern nursing. Feminist champion. Celebrity entrepreneur. Passionate statistician. Political operator. Data visualization pioneer. Florence Nightingale was all of these, yet none capture Nightingale’s seminal effect — something better felt through her prose:

It is as criminal to have a mortality of 17, 19, and 20 per thousand in the Line, Artillery and Guards, when that in civil life is only 11 per 1,000, as it would be to take 1,100 men out upon Salisbury Plain and shoot them.

The Englishwoman who wrote take 1,100 men out upon Salisbury Plain and shoot them. That’s the Florence Nightingale I want to understand.

• • •

Heroic design begins with a plan for selfless victory. It is accomplished with the courage to see the plan through. Nightingale tackled some of the ugliest problems her society had to offer. If we see the problems she endeavored to solve then we may begin to better appreciate her victories.

Before Nightingale, the sick were cared for by untrained widows, ex-servants, and paupers. These dissolute “nurses” were dismissed by Charles Dickens as incompetent, corrupt, and more interested in gin than patient welfare. Religious orders served the sick only marginally better: their holy focus was to prepare souls for judgment, not effective medical reform.

Crimean War Hospital at Sebastopol showing appalling conditions. Detail of wood engraving after E.A. Goodall, 1855. Credit: Wellcome Collection.

Before Nightingale, disease destroyed military campaigns. Hospital barracks overflowed with waste. Linens returned from the laundry with vermin. Red tape choked the arrival of meager bandage and food supplies. Dying patients crowded on floors of blood-soaked straw. Dysentery, cholera, and typhus raged mortality rates to levels that exceeded London’s Great Plague. In 1995 Howard Wainer quipped, “for the British soldier the least dangerous aspect of the Crimean War was the opposing army.”

Before Nightingale, women died more often giving birth in hospitals than at home. Sex workers were compelled to invasive (and totally ineffective) inspections for disease. Surgical outcomes were not understood in any coherent manner. Colonial natives “gradually disappeared” — died — as they came into contact with British civilization.

Worse, without data, only an anecdotal feel for these problems was accessible. Before Nightingale, we were in the dark.

• • •

Her backstory reads like a “chosen one” epic. Nightingale was born to landed gentry (1820, in Florence) and raised on family estates (in England). Her progressive father had her tutored in the classics — not uncommon for wealthy daughters of the day — but also the tools of power: mathematics and writing.

“above all the religious sculptures of Abu Simbel” (FN 1872)

On trips through Europe, Nightingale displayed a natural inclination to record data: distance and times traveled were neatly cataloged in her journal. She hoarded information pamphlets, especially those concerning laws, social conditions, and benevolent institutions. In a Parisian salon, Mary Clarke showed Nightingale how bold, independent, intelligent, and equal to men a woman can be.

In Egypt, Nightingale cruised the Nile and discovered ancient mysticism. Near Thebes, God called Florence Nightingale to nursing. God called me in the morning and asked me would I do good for him alone without reputation. But rich kids do not become nurses. Nursing was below Nightingale’s class. Her family disapproved.

Described as attractive, slender, and graceful, young Nightingale was wooed by genteel suitors. But she determined early that a life arranging domestic frippery would not satisfy her “moral” and “active” nature. Why have women passion, intellect, moral activity — these three — and a place in society where no one of the three can be exercised? Conventional marriage seemed like suicide.

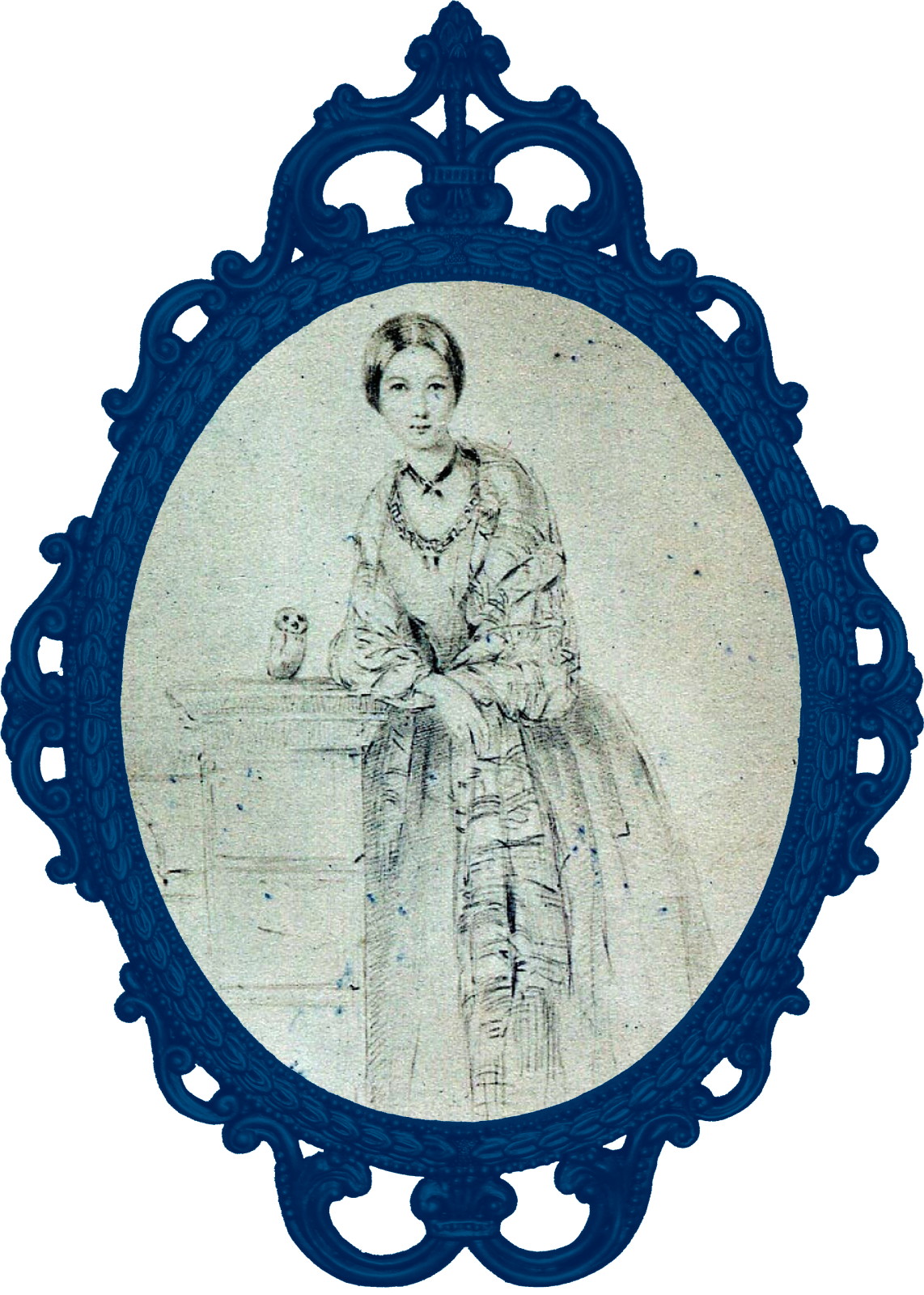

Florence Nightingale with her tame owl Athena, drawn by her sister Frances Parthenope Verney, Lady Verney (née Nightingale) c. 1850. Source.

Nightingale fled to Düsseldorf where she enrolled in a short nurse training program. It was the beginning of a multi-country progression through clinical and administrative nursing roles. After years of self-directed study and escalating responsibilities, Nightingale became the superintendent of a London women’s hospital.

In 1853, Russia invaded Ottoman territories and Western Europe took notice. The Crimean War was aflame. Soon the British public became enraged by press reports from the first modern war correspondents: the field hospitals were killing British soldiers faster than the enemy. A high death toll and deplorable barracks were credited to sloppy administration. The opportunity of a thousand lives opened for 34 year-old Nightingale: an emergency nursing effort would be mounted. Her administration experience prepared her as well as anyone to lead the expedition. A family friend helped deliver the appointment: Superintendent of the Female Nurses in the Hospitals in the East.

Nightingale with wounded soldiers in a ward at the Barrack Hospital Scutari, 1855.

Nightingale’s action in Crimea created an icon: She raised independent philanthropical funding for her operation. She recruited and trained a company of nurses and held them to strict discipline. She designed a pre-fabricated hospital ward and shipped it to theater. She built her own hot laundry, kitchens, and supply lines. Above all, Nightingale recognized that Administration saves more hospital patients than the best medical science. Years before the germ theory of disease was confirmed by Louis Pasteur and Joseph Lister, Nightingale enforced an obsessive commitment to sanitation. She, along with Ignaz Semmelweis, is considered a pioneer of hand washing. And all the while, Florence Nightingale was recording data.

After the war and back in England, Nightingale befriended William Farr, a physician, statistician, and data visualization pioneer. He helped her recognize the potential of the data she assembled in Crimea. They collaborated across a storm of statistical design innovations. Nightingale became obsessed with data quality and standardization. She orchestrated multi-year data collection efforts across the world using model survey forms of her own design. She considered the impact of secondary influences and developed a talent for posing provocative hypotheses. She became wary of the unintended harmful results of well-intentioned reform, often describing how the establishment of a foundling hospital for abandoned infants may result in an increase in the abandonment of illegitimate children.

The Nightingale Home and Training School for Nurses opened its doors to trainees in July 1860. Credit: Wellcome Library.

Nightingale raised over £40,000 by 1859 and used this money to set up the Nightingale Training School at St Thomas’ Hospital. She trained nurses and sent them, and her ideas, all over Britain and onward to America. She wrote hundreds of publications including Notes on Nursing, a best-seller that helped secure financial independence. Nightingale was admitted to the Royal Statistical Society and American Statistical Association. In 1861, the US Army consulted her about caring for their Civil War casualties.

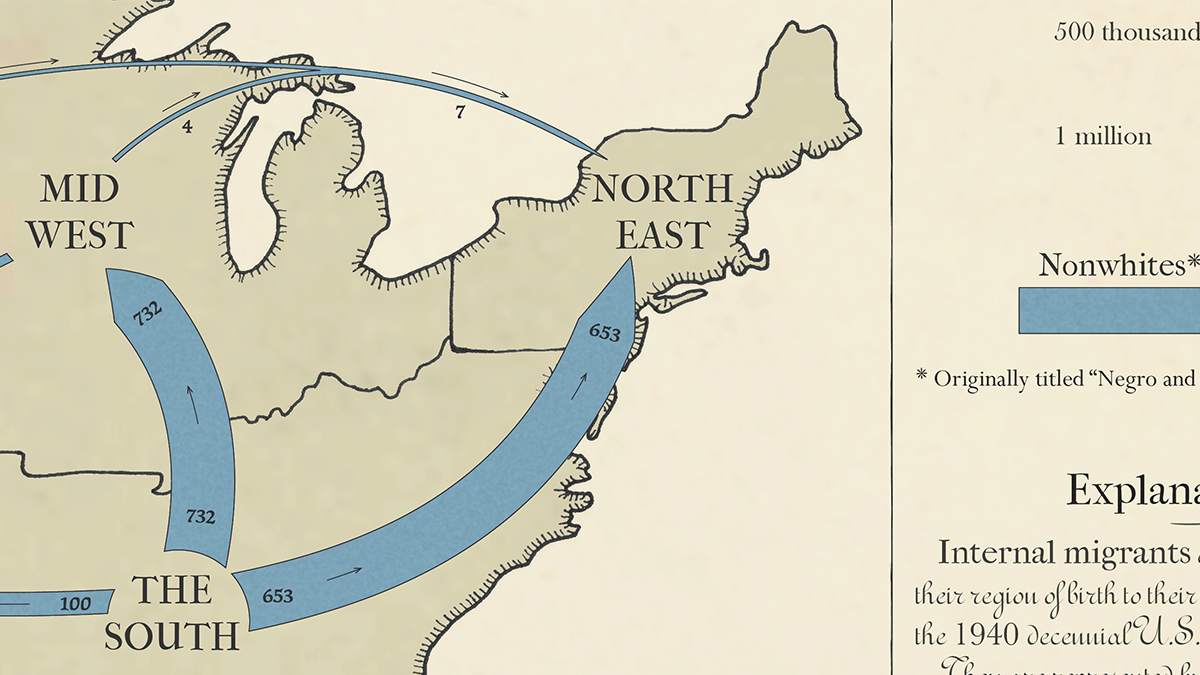

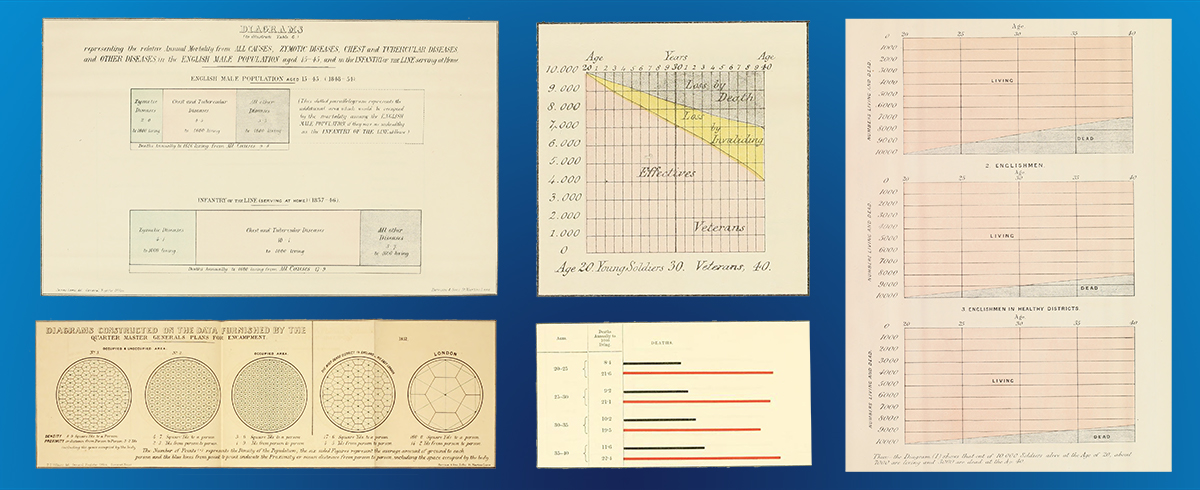

And Nightingale made data visualization, lots and lots of data visualization. She created bar charts, stacked bars, honeycomb density plots, and 100% area plots:

Diagrams from “Mortality of the British Army: at home and abroad” 1858. Source.

Incredibly, many of her charts go beyond historic description. Nightingale’s data visualization is prescriptive, designed to indicate required reform. She invented a new chart form to advance her arguments: a comparative polar-area diagram known today as the Nightingale rose (she called them “wedges”).

Nightingale published three rose diagrams at the end of the 1850s, after returning from the Crimean War and analyzing her mortality data with Farr. At the time, England’s Chief Medical Officer, John Simon, asserted that the great mortality from important classes of zymotic disease is practically unavoidable. Nightingale’s broad goal was to show that death from epidemic disease was preventable by known interventions that should be implemented in all hospitals.

Seeing all of her roses together can help us understand how Florence Nightingale built graphic arguments from easy-to-understand comparisons. Her most famous design, used twice, breaks a two-year timeframe into a pair of roses. The break occurs at the commencement of sanitary improvements and emphasizes by difference in size the effectiveness of these improvements.

In addition to that macro comparison, this first diagram also convinces you how much more deadly military barracks are compared to the industrial city of Manchester, notoriously unhealthy at the time. Manchester mortality rate is represented by a constant inner circle:

Diagram of the mortality in the British Army in the east during April 1854 to March 1855 (right) and April 1855 to March 1856 (left) in comparison to that of Manchester, represented by the circular dotted line. Credit: Wellcome Collection.

In her most famous pair of roses, below, Nightingale instead examines the causes of such high Army mortality. See how many more soldiers die of preventable disease (blue) than battle wounds (red):

Diagram of the causes of mortality in the army. Credit: Wellcome Collection.

Finally, in the below singular rose, Nightingale shows you the effectiveness of her sanitation ideas by comparing mortality rates before and after her interventions. Note the Commencement of Sanitary Improvements annotation at 9 o’clock and subsequent clockwise decline in hospital mortality. The constant inner circle now represents military hospital mortality in and near London, perhaps a more reasonable target than the city of Manchester:

Diagram showing mortality in hospitals at Scutari & Kulali. Credit: Wellcome Collection.

Once you read the roses, it is hard to deny her problem-solution argument. Critics suggest that her mortality data is better shown in something more straightforward like a bar chart. But this is not true: Florence Nightingale made lots of bar charts. No one cares about them! Her roses gripped 1858 readers and they still hold our attention today.

The Nightingale rose is a distant descendent of wind roses and compass roses found on navigation maps. It likely references André-Michel Guerry’s simpler 1829 cyclical plot of meteorological data. Her roses are beautiful, but please do not call the Nightingale rose a “coxcomb”: that word refers to her 1858 collection of her charts, named because together they were more striking than tables and text, as a rooster’s coxcomb is salient to a hen.

• • •

Nightingale’s “big bad” — the underlying malicious force consistently against her — was an entrenched class of elite doctors and Army officers. They resisted change in fear of admitting their own neglect, errors, and incompetence. These skeptical men resented Nightingale because she was an independently-financed civilian who did not answer to official military and medical hierarchies. Worse, she was a woman.

The three things that all but destroyed the army in the Crimea were ignorance, incapacity, and useless rules; and the same thing will happen again, unless future regulations are framed more intelligently, and administered by better informed and more capable officers.

British Lt. General Sir George Brown & officers in Crimea. Roger Fenton, 1855. Source.

How did Nightingale elicit reform? She believed statistics would give her an advantage. Her letter archive is packed with data requests. Data helped her achieve a better grip on the problems sending thousands to early graves, yes. But her data also helped defuse opponents — whose competing numbers were relatively sparse and outdated. She did not stop at definite knowledge. She recognized data’s limited ability to compel others to action. Nightingale stretched beyond the numbers to more political tactics. It was her persuasive talents and extraordinary will that marshaled her solutions into existence.

Florence Nightingale was a marketing machine. She knew a performance was needed to persuade. Nightingale used simple language and bold graphics to popularize her findings. Graphics helped attract and hold attention: printed Tables & all in double columns I do not think anyone will read it. None but scientific men ever look in the Appendix of a Report. And this is for the vulgar public. No one frames a table of data and hangs it on the wall. But people do frame maps. Florence Nightingale framed her own mortality diagrams, delivered them to influential VIPs, and commanded they be hung in their offices for all the vulgar public to see.

The Nightingale Jewel given by Queen Victoria to Florence Nightingale in 1855. Designed by Prince Albert, it stood as a badge of royal appreciation in the absence of a medal or established decoration suitable for presentation to a female civilian. © National Army Museum.

Nightingale self-published hundreds of titles. She sent her publications to the War Offices, the Commander-in-Chief, Members of both Houses, Commanding Officers, doctors, and Queen Victoria (who, along with Prince Albert, was a big fan). She became a populist hero through a constant presence in newspapers and periodicals. When her status as a woman would have been publicly unproductive, she wrote anonymously. Behind the scenes, she advised on the creation and operation of Royal Commissions that benefited her cause.

Her dramatic prose included the 1863 title “How People May Live and Not Die in India.” In 1871, she wrote about the finding that more women died delivering babies at hospital (and in contact with medical trainees) than at home. Training hospitals, she argued, must be as safe as home deliveries, else they would ensure killing a certain number of mothers for the sake of training a certain number of midwives. She gave an exhaustive tour of European hospital architecture in “Notes on Hospitals”, which begins: It may seem a strange principle to enunciate as the very first requirement in a hospital that it should do the sick no harm. It is quite necessary, nevertheless, to lay down such a principle.

• • •

The more I learn out Florence Nightingale, the more mysterious she becomes. From a wellspring of genuine sympathy for the sick, a true iconoclast emerges. Nightingale revered statistics as a religious experience. To her, data analysis revealed the character of God.

Nightingale believed social science — then called “social physics” — would help determine the laws by which our moral progress is to be attained. Patterns only observable by the aggregation of data could make known the road we must take if we are to discover the laws of God’s government of His moral world. Nightingale’s zeal was focused by her study of, and eventual dialog with, Adolphe Quételet. Moral statistics pioneer and champion of social physics, Quételet believed “it is society which, in some way prepares these crimes, and the criminal is only the instrument that executes them.”

Nightingale’s devotion was as practical as it was saintly. To serve God is to serve mankind, and to serve mankind required accounting for social-environmental causality. Sin is a function of the system, not just freewill. The means to prevent crimes and illness are at hand, if we did but observe… From the past we may predict the future. It is possible to exchange original sin for original goodness. The key to good health was not freewill. The key to good health was to give children a good start: nutrition, safe water, clean housing.

Nightingale believed God had clearly marked her out to be a single woman. She held fellow women accountable for their recline to domestic servitude in the face of opportunities for economic independence. A woman alone, Nightingale’s closest colleagues were men. She self-referentially identified as a man of action and a man of business.

‘’Miss Nightingale’s hair had been cut short after an illness.” Pencil portrait sketch by Colonel George Cadogan, 1856. National Army Museum.

As if Nightingale’s obstacles were not stacked high enough, she also persevered through a lifelong crippling disease. She contracted “Crimean Fever” during her iconic service. While at war she suffered a series of attacks, became deliriously ill, weak, and experienced severe sciatica, dysentery, rheumatism, earache, continual laryngitis, insomnia, and obsession.

The beautiful woman who charged to Crimea returned gaunt and with a noticeably disturbed personality. Nightingale’s mission was warm, but she was described as cold, stubborn, heartless, and tyrannical by her closest allies. She found fault in an assistant’s absence as he was dying.

Nightingale might be history’s most famous shut-in. Symptoms plagued her for most of her productive career. She operated her revolution from the confines of a couch, wielding a pen. She spent six straight years bedridden. Nightingale experienced weakness, headache, nausea at the site of food, breathlessness, tachycardia, palpitations, precordial pain, and neuroses. Worse, many thought she was faking her symptoms to attract more attention. Recently, the British Medical Journal published that Nightingale probably suffered from severe chronic brucellocis: a bacterial infection likely contracted from drinking bad goat’s milk in Constantinople.

I cannot imagine slogging through everything stacked against Nightingale, let alone persisting against it all to achieve so much. What might Nightingale want to say to us today? We do not have to guess. In 1890, at age 70, she made an Edison wax cylinder recording to be heard once she was no longer even a memory:

“When I am no longer even a memory — just a name, I hope my voice may perpetuate the great work of my life. God bless my dear old comrades of Balaclava and bring them safe to shore.” — Florence Nightingale, 1890.

• • •

The light of Nightingale’s lamp in Longfellow’s 1857 poem brings hope to her patients: Lo! in that house of misery / A lady with a lamp I see. Yes, she did round on patients in the dark of night — by the light of day she was consumed with establishing and running sanitary hospital barracks.

Florence Nightingale wielded a concert of design disciplines, at least: strategic, communication, organization, service, architecture, information, financial, and graphic design. However, it is not the technique of her crafts that makes her a hero. It is how she integrated them in successful service of her noble goal: hospital reform. The vision of Longfellow’s “lady with a lamp” resonates differently with me now. The photons of Nightingale’s lamp are outshined by the metaphorical light she poured into the world through her vision and accomplishments.

I have glimpsed the lady with the lamp and her light still shines. It is a light of rational optimism: We have the duty to strive for a decent world. In Nightingale’s words, the endless vista of improvement. Her light reminds me of what Hans Rosling called “possibilists” — people with a clear idea about how things are and a conviction and hope that future progress is possible. We have the power to continuously improve ourselves by observation and the use of reason. Properly put to work, they have and can continue to help us progress toward a way of life that is free and beautiful for all people.

On top of the statue of Florence Nightingale in her hometown, two Latin words are chiseled into stone. FIAT LUX: LET THERE BE LIGHT.

Florence Nightingale statue, Derbyshire England. See what her real lamp looked like here.

• • •

RJ Andrews once made a miniature coxcomb for his Florence Nightingale doll:

Here she is! Florence Nightingale reunited with her coxcomb, full of convincing #dataViz including one very famous polar area chart. pic.twitter.com/Z8sYCVxFod

— RJ Andrews (@infowetrust) December 31, 2017

• • •