"An Appeal to the Eye"

William Playfair promotes his charts.

RJ Andrews

Sep 22, 2020 • 11 min read

In 1801 William Playfair published The Statistical Breviary. Its original advertisement still attracts curiosity: "a farther Extension of the System of appealing to the Eye, in order to compare with Ease and Accuracy proportional Quantities...." The Breviary expanded on his earlier landmark work, 1786's Commercial and Political Atlas. Together they introduced nearly all the basic forms of modern statistical graphics.

Playfair published the Breviary at the outset of the Napoleonic Wars. It was a time of violent change across Europe's nations. The Breviary evaluated the power of nations by comparing their land areas, populations, and revenues. Its "statistical" focus blended both our modern understanding of the word and its "statecraft" origins.

I find Playfair's words as interesting as his graphics. He explains the power of charts, citing advantages for engagement and learning that still ring true. The following text is the preface to Playfair's Breviary, formatted for web reading. I've removed some ligatures and moved footnotes to the margin. Two images illustrate Playfair's text, but the emphasis of this re-publication is his words. Recommendations for how to see all of the charts follow. -RJ Andrews

THE STATISTICAL BREVIARY

By William Playfair, 1801.

PREFACE

Having about a year ago been requested by the English editor of Mr. Boetticher's Statistical Tables, to consider of some method of bringing them down to that period, without injuring the original work, I proposed to make a supplementary table, comprehending all the countries which have undergone any material change since the publication of the book. I then undertook to make out such a supplementary table; which I did, and it is published at the end of that work.

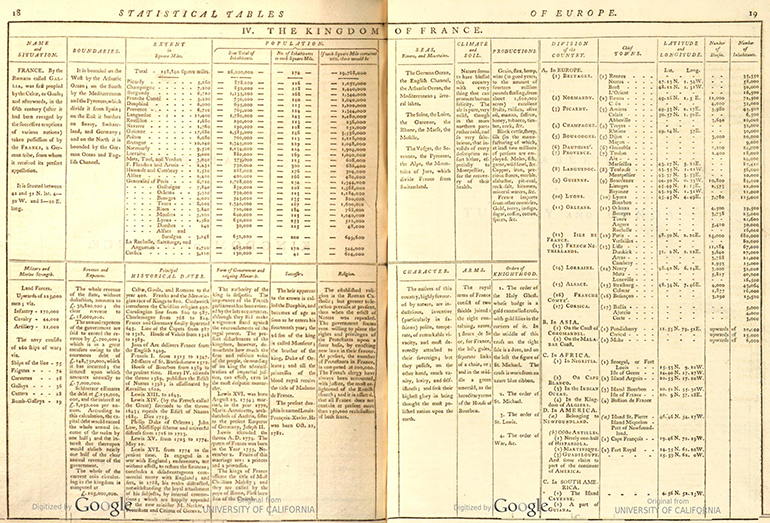

One of Playfair's tables from the 1800 translation of Boetticher. See them all at HathiTrust.

In the course of executing that design, it occurred to me, that tables are by no means a good form for conveying such information, unless where a number of different countries are intended to be exhibited at once. Where there is only one to be set forth, I can see no kind of advantage in that sort of representation, while the inconvenience of a large size, in a book that is intended to be frequently referred to, is obvious.

I do not conceive that it is in any manner the province of statistical works to contain historical relation, or any thing that is not a simple fact and relative to one single epoch or date. The numbers of people, quantity of ground, revenues, prices of labour, &c. as simple and useful facts, belong to statistics; but the description of the order of the garter, or of the golden fleece, has nothing to do with it. To encumber statistical reports with such information appears to me to be ill placed, and as such improper.

I have composed the following work upon the principle of which I speak; this, however, I never should have thought of doing, had it not occurred to me, that making an appeal to the eye when proportion and magnitude are concerned, is the best and readiest method of conveying a distinct idea.

Statistical knowledge, though in some degree searched after in the most early ages of the world, has not, till within these last fifty years, become a regular object of study. Its utility to all persons connected in any way with public affairs, is evident: and indeed it is no less evident that every one who aspires at the character of a well-informed man should acquire a certain degree of knowledge on a subject so universally important, and so generally canvassed.

Geographical knowledge has long been considered as necessary for persons of both sexes who wish to acquire any tolerable degree of general information; in so much that, next to ignorance of the grammar of one's native language, nothing betrays want of information so soon as ignorance in matters of geography, without which it is almost impossible to carry on conversation long on any general subject.

Geography is, however, only a branch of statistics, a knowledge of which is necessary to the well understanding of the history of nations, as well as their situations relatively to each other. In ancient history, and even down to our own times, there is nothing so imperfect as the accounts given of statistical matters. Ancient historians, and other writers, tell us for example, of great armies raised and great achievements performed; but concerning the finances, and ways and means, they are generally silent. To the importance of this species of knowledge, mankind have only of late years begun to pay a sufficient degree of attention, the want of which, hitherto, leaves us now in great ignorance on many points which it would be very useful for us to know, in order to form a comparison between the ancient state of the world and its present situation.

Statistical accounts are to be referred to as a dictionary by men of riper years, and by young men as a grammar, to teach them the relations and proportions of different statistical subjects, and to imprint them on the mind at a time when the memory is capable of being impressed in a lasting and durable manner, thereby laying the foundation for accurate and valuable knowledge.

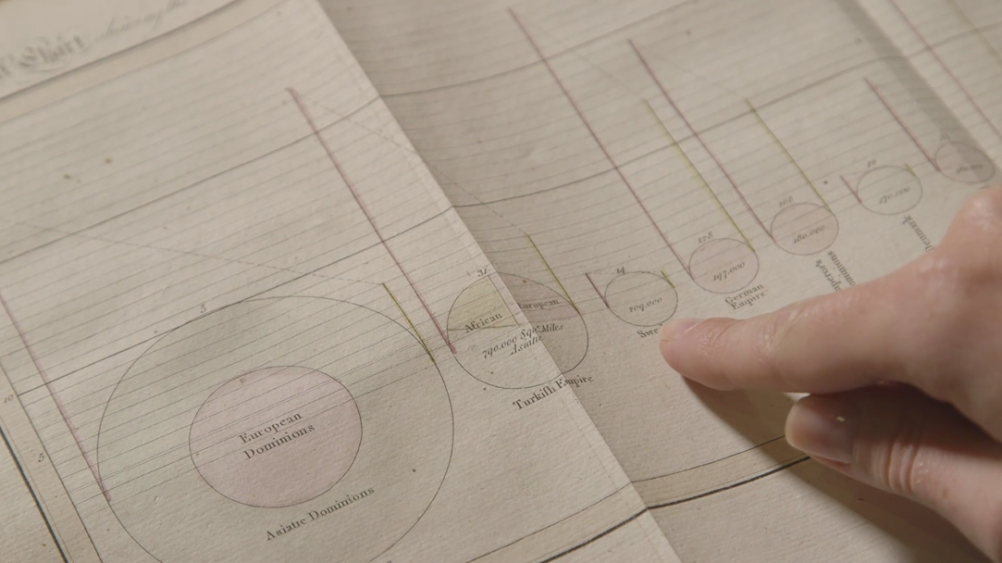

Since the value of this study is generally acknowledged, it has become a desirable thing to render it as easy and perfect as may be. In the introduction reasons are given for adopting the mode of representing the magnitude of different countries by proportional circles, but the great tell of its utility is in the mind of the person who takes up the charts. The first of these has been shewn to numbers of persons, all of whom have declared that till they saw it, they had no right and distinct idea of the proportional extent of the different countries such as it gave them. The reason of this is evident: for, as it is not without some pains and labour that the memory is repressed with the proportion between different quantities expressed in words or figures, many persons never take that trouble;— and there is even, to those that do so, a fresh effort of memory necessary each time the question occurs. It is different with a chart, as the eye cannot look on similar forms without involuntarily as it were comparing their magnitudes. So that what in the usual mode was attended with some difficulty, becomes not only easy, but as it were unavoidable.

Whatever presents itself quickly and clearly to the mind, sets it to work, to reason and think; whereas, it often happens, that in learning a number of detached facts, the mind is merely passive, and makes no effort further than an attempt to retain such knowledge.

Detail of Plate 1 showing Russia (left) and Turkish Empires. See them all at HathiTrust.

It would be almost impossible for any person of intelligence to contemplate the first chart without being struck with the great size of Russia and Turkey, and the comparatively small extent of those countries which have borne the principal sway in the world for these last five hundred years, whilst Russia was nearly unknown, and counted but as dust in the political balance of nations. Some general conclusions, accompanied with no small degree of surprise, naturally attend the first view of this proportional chart of nations.

What thinking man who considers the important part that the small republic of Holland has acted, while Russia lay as if congealed in an eternal winter, but will conclude, that if ever the people in those different countries come to be in any degree similar in civilization and intelligence, the importance of the smaller must sink into great inferiority, and in general, that if even the different countries in the world should come to be nearly upon a par in respect of arts, civilization and knowledge, the scale of their importance must be strangely altered, and accordingly it is daily altering: for, as commerce, arts, and civilization, have been making great progress during the last century, the foundation of changes has been solidly hid, and their have begun to take place with unexampled rapidity.

Holland, which was a preponderating power in the beginning, and during a great part of the last century, as it had long before been, entered into the last war shorn of its importance, with the rank of only an auxiliary to France and Spain. It did not long preserve even that diminished rank; for having first submitted to be the tool of a French faction, it was in the course of a few days reduced to obedience by the King of Prussia, who acted with it just as he would have done with a rebellious province of his own dominions; and when the present war broke out, it soon was reduced to what impartial truth obliges us to call a dependant province of France.

Portugal, now so different from what it was in the time when its conquests almost encircled, and did astonish the world, seems to run a risque of sharing the fate of Holland.

Though extent of territory is the ground work of power, as it regulates in a great degree the population of a country; yet we find neither extent nor population will do without revenue: hence we find Poland extensive, populous, rich in soil, and productive, peopled with a race much more zealous of liberty than any of the neighbouring kingdoms, fallen a prey to the power of those very neighbours. The conclusion is, that want of revenue was the cause of its ruin*.

* Perhaps it will be urged that want of unanimity, not want of revenue, ruined Poland; but in answer to this, it may be urged, that want of revenue occasions want of unanimity as well as many other wants.

To render statistical accounts accurate and complete, it is not sufficient that individuals should collect knowledge, and arrange it in order, for the aid of rulers and magistrates. An habitual and regular practice of collecting information, both generally and locally, is necessary; but as vanity is not flattered by employing men to collect such materials, as it does not immediately advance the interests of those who are at the head of affairs, it is to be feared that the business will long be left to the inadequate care of a few individuals.

Where vanity is not gratified, or interest promoted, knowledge is generally neglected. The bushels of rings taken from the fingers of the slain at the battle of Cannae, above two thousand years ago, are recorded: so are the numbers of combatants at the battles of Agincourt and Cressy; but the bushels of corn produced in England at this day, or the number of the inhabitants of the country*, are unknown, at the very time that we are debating that most important question, whether or not there is sufficient subsistence for those who live within the kingdom. We neither know whether the country is increasing or diminishing in population: we are equally ignorant as to its produce, and yet, perhaps, no nation in Europe is better informed on those important subjects than ourselves. No encouragement is given, no proper steps are taken by those who rule, to ascertain points that are so material, while there are Societies instituted for inquiry into matters which are past and gone, rare and useless, or distant and unknown.

* Some efforts have been lately made to ascertain the population of this country, which are entirely inadequate to the purpose, and are therefore to be considered as nothing.

Were the aid and support of public men obtained in collecting statistical knowledge, great progress might be made in it at little expense, and with great facility; but so long as that is not the case, individuals will find themselves reduced to the situation of scanty gleaners, not that of men carrying home an ample harvest.

Statesmen, and those in power, would in the end find themselves amply repaid for any trouble, or moderate degree of experience, that an attention to statistics might occasion; for by that means the operations of government (particularly the revenue department*) would be greatly facilitated. Great statesmen and monarchs have known this in all ages; from whence attempts have arisen to number the people, and take an account of property, &c.

As statistical results never can be made out with minute accuracy, and that, if they were, it would add little to their utility, from the changes that are perpetually taking place; it has been thought proper in this work to omit that customary ostentation of inserting what may be termed fractional parts, in calculating great numbers, as they only confuse the mind and are in themselves an absurdity.

* In the revenue department much accuracy and great attention prevails throughout; but all other national operations are done in a slovenly inaccurate manner, at if revenue alone were worth attending to: it is not so in many countries that are in other respects much worse regulated than this.

Statistical books, like dictionaries, require new editions from time to time, as changes take place among nations; but it is impossible to begin a regular series of such accounts from any period so proper as that just previous to the present war. Europe had been almost stationary for a century, when all at once changes commenced, which, from their nature, their causes, and the general situation of things, will not soon be ended in a solid manner. The first view of European nations is the foundation from which we rise, with an intention to exhibit in a like manner the same nations under the different vicissitudes which the present troubles have occasioned, or in future may occasion.

ADVERTISEMENT

In the observations made relative to the utility and fitness of large tables for conveying statistical information, no idea was entertained of objecting to the merit of M. Boetticher's work; but from inspecting those tables themselves, it will appear, that except in regard to Germany, which is divided into a great number of governments, in the VIth table, where eight states are represented at once, and in the last supplementary table, where eleven different nations are contained, there is more inconveniency than advantage arises from the form adopted.

With respect to throwing aside the units, tens, and hundreds, in great numbers, it is done under this simple impression, that as the information does scarcely ever come within a thousand of the truth, it is an affectation of accuracy beyond what has really been attained; or, to make a fair comparison, it is like a historian giving as truth, an account of the private minutiae of courts and embassies, which were known only to the parties themselves, and though reported publicly never believed. No sort of reflection is however meant on those who think fit to give their statements in the other way, although the number of figures certainly embarrasses the memory without answering any good purpose.

Playfair's preface is followed by an introduction and then a sequence of gatefold charts, each accompanied with explanatory text and reference data table. The best way to experience these is by purchasing Ian Spence and Howard Wainer's republication (Amazon). It packages both Playfair's Atlas and Breviary with Spence and Wainer's inspiring analysis.

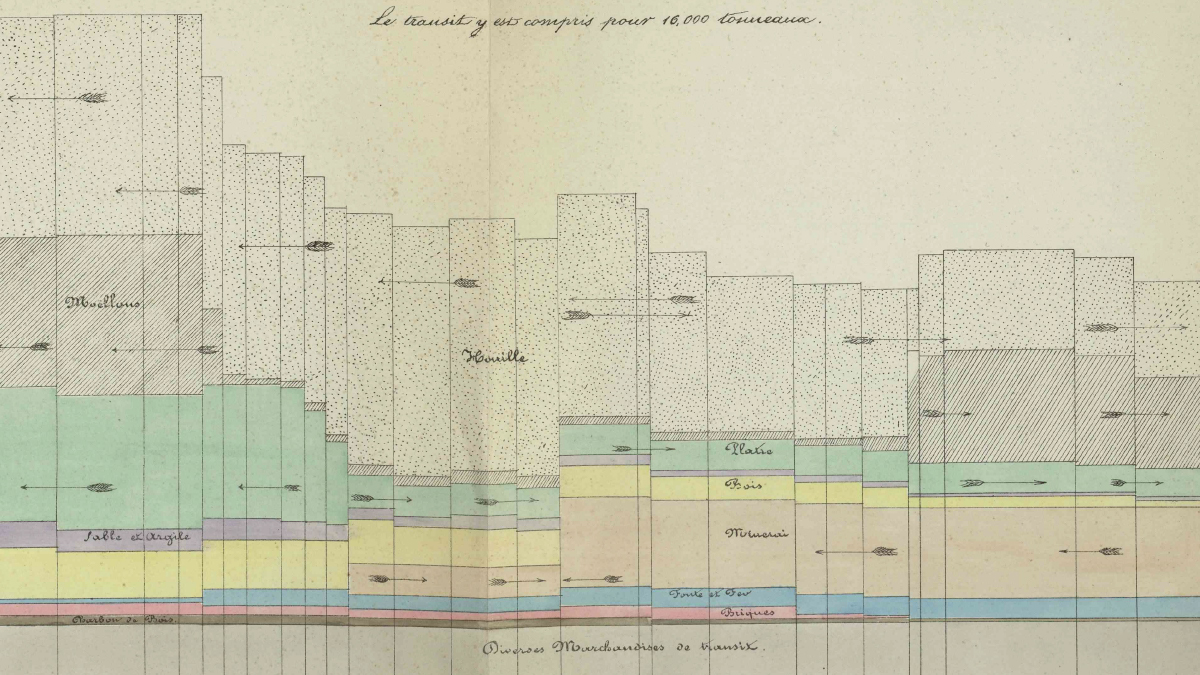

You can read the entire third edition of Playfair's Atlas online at archive.org. Reading the Breviary online takes a little more effort. The text is available on archive.org, but it is missing the charts. David Rumsey's beautiful images of the French translation is the best place to see them all in once place.

The banner image and detail of Plate 1 are from the University of Edinburgh.